The French Dispatch (2021): An Imaginative Look at Journalism

Wes Anderson, one of the most creative directors of the past twenty years, is back at it again with his newest film, 2021’s The French Dispatch, featuring his famous usage of wide shots, theatrical elements, the color orange, and the actors Owen Wilson and Bill Murray. Is it any different from his other films? Let’s find out!

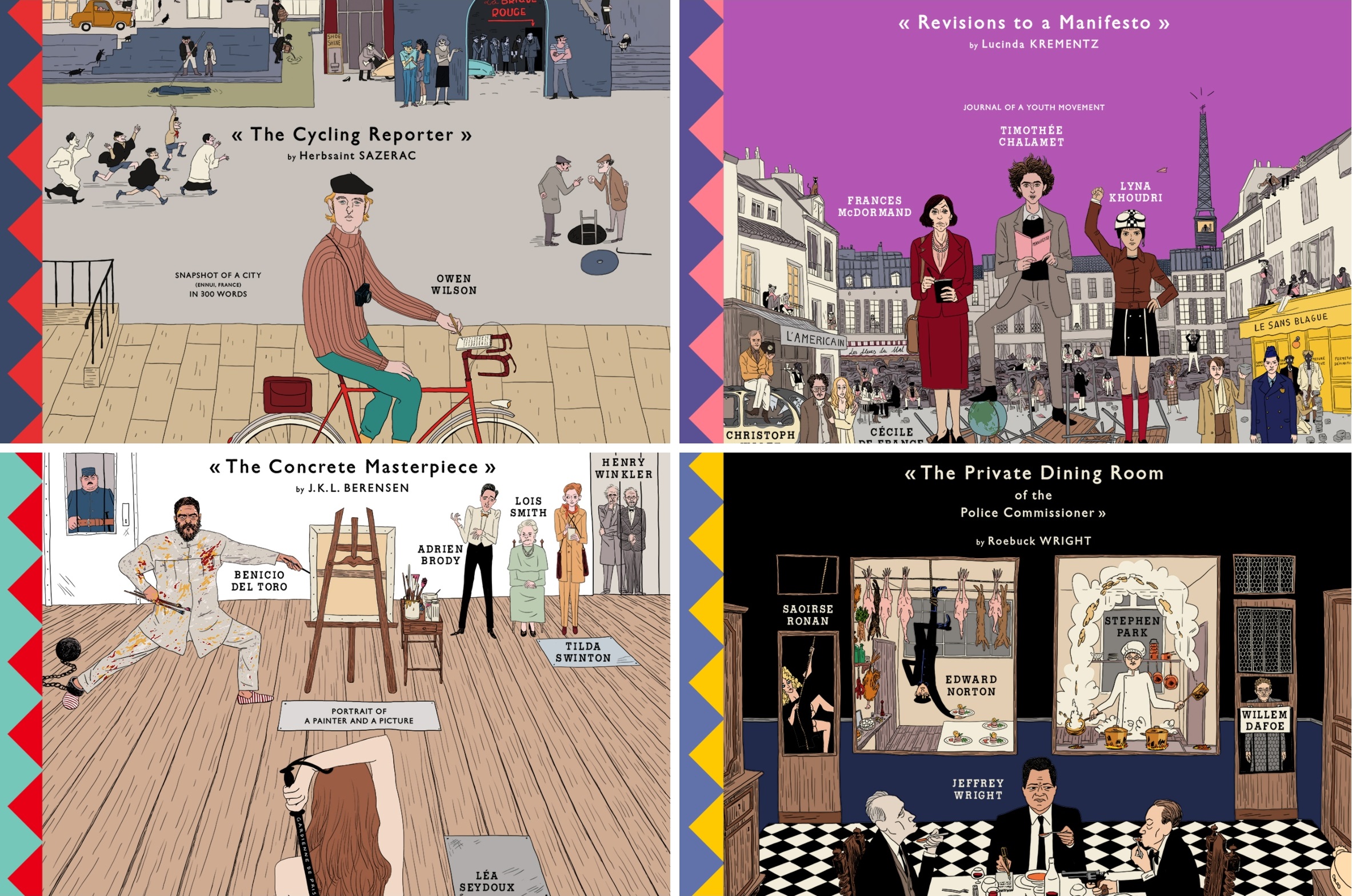

The film talks about four different stories surrounding a journalist, an artist in prison, a student activist, and a police rescue of a boy. In the first story, a reporter (played by Owen Wilson) cycles around Ennui-sur-Blase— the fictional French town where the titular magazine is located— while giving a tour of the city. He compares the past and present of each building and street block he encounters and explains how much and how little things have changed over time.

The second story (“The Concrete Masterpiece”) follows a writer of The French Dispatch (played by Tilda Swinton) as she gives a presentation on a prisoner named Moses Rosenthaler (played by Benicio Del Toro) who was locked away for murder. While in prison, he passes his time by painting a prison guard (played by Lea Seydoux). Eventually, he becomes famous enough that fellow inmate and art dealer, Julien Cadazio (played by Adrien Brody) buys his artwork and makes him a sensation in the art world. One day, Rosenthaler paints his magnum opus, however, he paints them on the walls of the prison. Angered, Cadazio gets into a physical fight with Rosenthaler, which later escalates into a prison riot. Rosenthaler stops the riot all by himself, and Cadazio learns to appreciate the art pieces and has them airlifted.

The third story (“Revisions to a Manifesto”) revolves around a journalist named Lucinda Krementz and her story on student activist Zeffirelli (played by Timothee Chalamet). Zeffirelli writes a manifesto for the student revolution, and he and Krementz have a brief romance. Tensions between the students and government arise, culminating in a chess match between the two forces. When the students fail to make a move, they are stormed and overrun. Krementz tells Zeffirelli to leave with a fellow student revolutionary, Juliette (played by Lyna Khoudri) and the two make love. Eventually, Zeffirelli is killed when he goes up to fix a broken radio antenna. After his death, he became an iconic figure associated with the student revolution similar to Che Guvera.

The final story (“The Private Dining Room of the Police Commissioner”) revolves around the police chief’s son being kidnapped by a criminal gang. To get his son back, the chief sends a fellow officer disguised as a chef to cook the gang a fancy dinner. Unknown to the gang, however, the cook laced the food with a deadly poison, and most of the gang perishes. However, the leader of the gang survives and escapes with the child. The police chase after him in a high-octane car chase sequence, ultimately culminating with the child escaping and reuniting with his father.

Back at the French Dispatch, the editor of the paper, Arthur Howitzer Jr. (played by Bill Murray) has died and the rest of the staff write a final piece to honor his memory.

I dislike speaking too much about Wes Anderson’s movies because too often I just devolve into calling him an auteur or whatever and that’s not what I’m after. I feel that the focus on the director as a singular artist with a singular vision whose films are his work and his alone detracts from the hard work that all the other people involved in a film contribute. So, credit where credit is due to cinematographer Robert D. Yeoman, editor Andrew Weisblum, production designer Adam Stockhausen, set designer Rena DeAngelo, and animation director Gwenn Germain for their contributions to the film.

The French Dispatch utilizes changes in aspect ratio and color order to punctuate emotional beats in the story. The three scenes are primarily shot in black & white, but change to color to highlight important moments such as the unveiling of Rosenthaler’s frescos or the color of a character’s eyes. Additionally, the framing devices of “The Concrete Masterpiece” and “The Private Dining Room of the Police Commissioner” both utilize color to imply that they take place in different time periods. Another dramatic shift comes in the form of the animated segment in “The Private Dining Room” which is used to convey the chase scene. Stylistically, it draws from European comics such as The Adventures of Tintin, and the bright colors help it stand out from the black & white that preceded it.

Anderson’s busy yet ordered sets are present as usual, most notably in the introductions of each member of the French Dispatch’s staff. I will say, one critique I have of this movie is the lack of utilization of many of these characters. Their introductions are so full of humor and intrigue that I wish they had been around longer. Some of Anderson’s best works (The Royal Tenenbaums and Fantastic Mr. Fox both come to mind) have large casts, so it’s not like it’s something he can’t do. Anyway, places such as Rosenthaler’s prison cell, the cafe where the student revolutionaries assemble, and the various locations in Ennui-sur-Blase that Owen Wilson’s character travels through. They feel simultaneously alive and frozen in time; artificially posed and structured yet bursting with life.

Love or hate his directorial style, there’s no questioning the influence that Wes Anderson has over “prestige” filmmaking in the 21st century. As the bridge between what’s seen as “artistic” and what’s popular in movies grows, he straddles an interesting midpoint; a director you can brag about enjoying on a first date without having to scour the Internet for somewhere to watch it. While his works may be divisive, there’s no denying his vision, and The French Dispatch is a well-crafted film that uses the director’s usual cinematic touches to tell a story that’s a love letter to reporters and journalists of past, present, and future, a group that is needed now more than ever.

Synopsis written by Michael Li.

Co-Written by: Michael Li